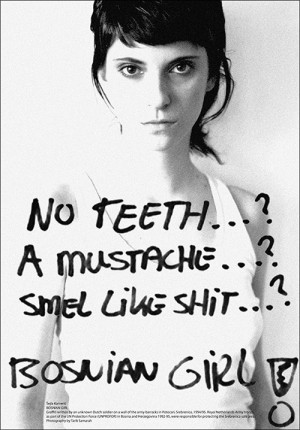

Šejla Kamerić

Bosnian Girl, 2003

b/w photograph, variable dimensions

public project: posters, billboard, postcards

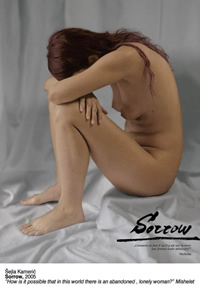

Sorrow, 2006

self-portrait, colour photograph

light-box, 177×133 cm

Born in 1976 in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. She completed studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sarajevo, Department of Graphic Design. Until 2000 worked as Art Director in the creative team “Fabrika” in Sarajevo. Since 2002. she has been a member of the European Cultural Parliament. She uses photography and video as media juxtaposing an explicit social context with intimate perspectives. Public interventions, diverse types of actions and site-specifically installations are one of the most important aspects of her approach to art (EU/Others, Fortune Teller, Bosnian Girl). Along with her fourteen solo shows, interventions and actions in the public space, she has exhibited nationally and internationally at group exhibitions, from the 1st Annual Exhibition of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art “Meeting Point” (Sarajevo, 1997) to the 15th Sydney Biennale “Zone of Contact” (Sydney, Australia, June-September 2006). She also participated in artist residency programs. Works in the field of graphic design, theatre, movie. Šejla Kamerić belongs to the generation of Sarajevo artists who grew up in the war under three-and-a-half year’s long siege and shelling of the city. This biographical fact has much determined the attitude of this artist, as well as her understanding and practicing art. Learning about life in the cruelest manner and knowing how to transform that she has lived into art is the essence of Šejla Kamerić work. There are two essential points in her work: Personal viewpoints based on common experience about the outside world: hot issues of the local society related (or in opposition) to the actual worldwide moral, socio-political subjects.

Self-reflections based on personal experience about the existential values: surviving the siege and shelling of her city she learned the fine line between life and death, to separate the essential from the unimportant, to recognize hierarchy of needs.

It means that for Šejla art is not the goal, but the means for self-identification – communicating own experiences, memories, and opinions – which she wants to share with or confront to the others. For one of her axiomatic works Bosnian Girl she says that it is directly connected to the Srebrenica tragedy, but that it deals with prejudice as well, not only by others towards us, but also by us towards others.

Dunja Blažević

Bosnian Girl is a B&W photograph featuring the portrait of the artist with the graffiti from the Srebrenica barracks written across it. A Dutch soldier first wrote the graffiti on the wall of the barracks in Srebrenica (The Royal Netherlands Army was stationed in Bosnia and Herzegovina as a part of the UN Peace Operation 1992-1995 and was responsible for the protection of the region). Referring explicitly to the events of the Srebrenica massacre, the artwork nevertheless invites us to leave behind this specific frame of reference. By juxtaposing the “Other” (the graffiti text) with “Oneself” (the body) in an evident non-dialogue – a linear confrontation of the extremes with the subjacent violence – the artwork breaks through to a new notion of identity, hybrid, impure, artificially and contextually conditioned. The body, presented in a linear manner (condensed to an attitude) incorporates the graffiti thus thriving to a new identity. The “final” Bosnian Girl (not the one from the graffiti, nor the personification through the artist’s image) exposes itself as a contradictory simulacrum of multiculturalism.

Bosnian Girl is a B&W photograph featuring the portrait of the artist with the graffiti from the Srebrenica barracks written across it. A Dutch soldier first wrote the graffiti on the wall of the barracks in Srebrenica (The Royal Netherlands Army was stationed in Bosnia and Herzegovina as a part of the UN Peace Operation 1992-1995 and was responsible for the protection of the region). Referring explicitly to the events of the Srebrenica massacre, the artwork nevertheless invites us to leave behind this specific frame of reference. By juxtaposing the “Other” (the graffiti text) with “Oneself” (the body) in an evident non-dialogue – a linear confrontation of the extremes with the subjacent violence – the artwork breaks through to a new notion of identity, hybrid, impure, artificially and contextually conditioned. The body, presented in a linear manner (condensed to an attitude) incorporates the graffiti thus thriving to a new identity. The “final” Bosnian Girl (not the one from the graffiti, nor the personification through the artist’s image) exposes itself as a contradictory simulacrum of multiculturalism.

Joško Tomasović

Excerpt form the text

Sorrow, the latest work by Šejla Kamerić, premiering at Sydney Biennale is a photograph featuring artist’s nude with a large inscription Sorrow in the low right corner followed by a quotation from Michelet: “Comment se fait-il qu’il y ait sut la terre une femme seule – délaissée?”

Sorrow, the latest work by Šejla Kamerić, premiering at Sydney Biennale is a photograph featuring artist’s nude with a large inscription Sorrow in the low right corner followed by a quotation from Michelet: “Comment se fait-il qu’il y ait sut la terre une femme seule – délaissée?”

The very fact that the artist chose to observe herself through Van Gogh’s (or Sien’s) lenses does not eradicate the inner perspective of her artwork, but rather demonstrates the degrees of complexity encountered through such a general act of self-observation. Beginning with Van Gogh’s indentation of the English title, transcribed literally in Kamerić’s remake, is not merely a sign of density of messages within the pictorial space, but could be considered a marketing strategy par excellence. Here, a shift is performed from Van Gogh’s “cartoon aesthetic” to a branded and polished contemporary image, which reaches nearly a “billboard” status. The Michelet’s rhetorical and emblematic Romantic question, copy-pasted to this new context, has an entirely different resonance.

Joško Tomasović

Excerpt from the text

So.ba – Opening

So.ba – Opening Sarajevo Center for contemporary art (SCCA)

Sarajevo Center for contemporary art (SCCA) Pro.ba

Pro.ba Opening of Soros Center for Contemporary Art Sarajevo

Opening of Soros Center for Contemporary Art Sarajevo